The best way to learn how to do something, whether it’s how to teach or how to care for children, is to learn from those who have already done it. Those individuals are called theorists, and their theories are the structures upon which much of the practice that you see around you was built. While all of these theories are extremely beneficial in your practice, it can be difficult to know how each one can be used effectively, especially if you’re new to the field of early childhood education and care.

Relate your observation back to theory

Whether you work with babies, toddlers, or preschoolers, you’re likely gathering lots of data about their development and behaviour. But can you explain why it happens? Child development theory is helpful for linking observations back to what’s happening at a deeper level.

Explain why this theory relates to your observation

You should take a hierarchical approach when linking theories to observations. This means that you should start by talking about big theories (those which are more universally accepted by those in your field), before moving onto smaller, more niche theories. Then, relate these theoretical frameworks back to your observation: Was it influenced by one of these theoretical approaches? If so, how?

Practical examples of linking to theorists

Some theorists are better suited for some contexts than others. Contexts where children have special needs or if you are working with a specific population (e.g., primary education, playgroup, preschool, etc.) will call for different approaches to observe.

There are some brilliant thinkers working in early childhood education and care, who’ve created theories we can look at when observing children. Let’s take a quick look at three theorists, before getting into how you can link them to observations.

Vygotsky believed that learning occurs through social interaction with others. Piaget thought that learning is a process of discovery and challenge; as he said, children do not think like adults because they lack adult knowledge. They think differently because they have a different kind of knowledge. And finally, Bruner said that learning is about understanding one’s environment; it takes place through making sense of things around us—and it begins from birth! We can use these frameworks to make sense of what we see in our day-to-day work.

As an example, let’s say we observe two three-year-olds playing together. One child has invented a game where she pretends to be a dog, while her friend pretends to be her owner. She barks orders at him (Sit!), which he dutifully follows (Sit!).

In terms of Vygotsky’s theory, she’s using language as a tool for social interaction: he has no idea why she wants him to sit down but does so anyway because she told him so. In terms of Piaget’s theory, she’s challenging his preconceptions about dogs and their owners by giving commands he would never expect from a human being. Finally, in Bruner’s framework, both children are trying to understand their world better by pretending to be something else entirely. This activity might seem silly at first glance—but it helps both children learn more about themselves and each other than if they were just sitting quietly on opposite sides of the room.

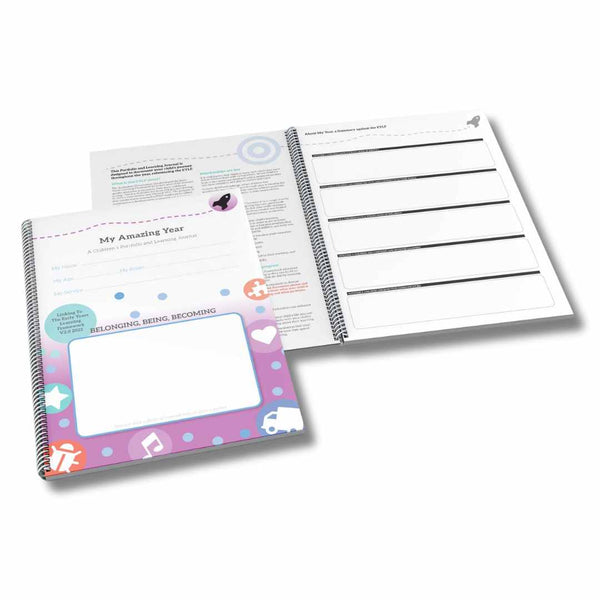

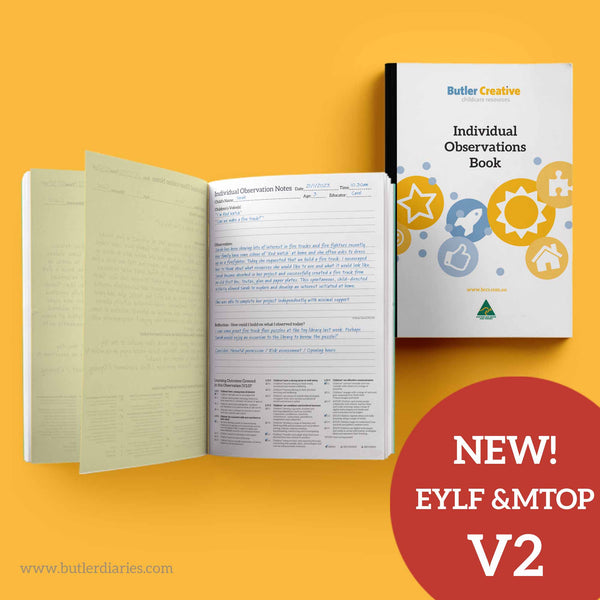

For more information on early childhood theorists and how they relate to the EYLF outcomes, visit 'Linking Theorists to EYLF Outcomes'. Our weekly programming and reflection books also include a theorist cheat sheet to assist you in linking your observations to theorists. You can view the programming diaries here.